Last year I started my Seasons of Growth experiment, and it was fantastic in a number of ways. This year I continued it, and decided to do a more full writeup for each season.

Season of Romance

At the start of the year I was realizing that my life seemed pretty perfect in most ways, with one major exception: I want to have a long term relationship and kids relatively soon. So I kicked 2022 off with a season attempting to go “all in” on finding a romantic partner.

The first things this included were making a Date Me page for my site, which gets decent traffic by the sorts of people I expect to vibe with on some level. I also made dating profiles on a few new sites, and tried the paid option on them and the ones I was already on, in an attempt to up my odds of actually getting good relationships from them. My longest running relationship to date (3 years) was from OKC, so online dating has been relatively good to me all things considered, even if it also involved years of not finding any LTRs.

I also spent more time going to events and activities to meet new people, such as Vibecamp and book clubs. Network effects of friends knowing that I was openly looking for a partner was also valuable for getting recommendations from them and getting set up on some dates and introduced to some people.

This season was also useful to focus on what I actually want, romantically, and prune away things that didn’t seem likely to get me there. Despite having both a mono side and a poly side, I realized that wanting to settle down and have my own bio kids within a couple years meant I needed to focus on finding a monogamous partner, or alternatively-but-less-likely a poly-primary-partner-who-wants-kids-specifically-with-me, and that meant not pursuing romantic interests that didn’t feel after a few weeks like they would move in that direction.

This felt like a cost at times, where I feel like I didn’t invest as much as I might normally have in relationships that could have been good/resulted in new deep friendships, but also was an important time/attention saving heuristic, I think.

Synergy: Season of Wealth helped me get over the “wasteful” cost of paying for the apps. This didn’t end up leading to anything enduring, but I’m still glad I did it, as I would have always wondered “what if” had I not. Season of Aesthetics obviously was helpful here too, not least of which because it helped lead to better pictures for my dating profiles!

Outcome: As of yet this season hasn’t accomplished its “primary objective,” but overall I’m pretty happy with how things went. I’ve gotten a gratifying amount of responses to my form, went on about a dozen dates from responders there and to my various dating sites. Most notably, through my Date Me Page I met a girl that I’ve been dating since. The current status of that is Complicated, but I’m hopeful, and no matter how it turns out I’ll always be glad we dated.

Season of Class

This season was a “second level” of sorts for Aesthetics. Part of Aesthetics was recognizing what my appearance signaled to others, but it focused a lot more on understanding and developing what I like and dislike. “Class” is more about the way others perceive someone and the ways behavior affects that, which includes their wardrobe choice, but is not limited to it. So I learned more about what clothing signals to others, and made some more minor adjustments based on that.

But the more valuable and central thing I developed was a better “outside view” on my behavior; not just how it represented who I appeared to be, but also how it affected those around me.

It’s worth noting that this is the first season where I felt something like a “push and pull” toward and away from the “goal” of the season. It happened a little with aesthetics, but part of what “unlocked” aesthetics for me was discarding the false belief that clothing had to be either comfortable and cheap or expensive and aesthetically appealing.

The less-obviously-false dichotomy here is the tension between caring what others think of you and being constrained by what others think of you. Most people around me my entire life have only ever demonstrated “caring what others think of you” in a way that was so clearly self-inhibitory, so clearly full of shame and joylessness and anti-life, that I decided from a young age that I wanted None of That, Thanks Very Much.

This extended beyond being embarrassed by things like dancing in public, or even interests and passions, such as my stepbrother having to hide that he was into anime when we were in high school so as to be accepted by his “friends.” The most clearly limiting effect of it seemed to be a prevalent lack of agency in others, particularly in unusual situations. I can’t count the amount of times I’ve been able to solve problems others thought ~impossible by simply ignoring the expectation of what people thought they were “supposed” to do based on social norms.

But I also realized that there were some things I did as a result of having this mix of high agency and non-shame that had negative consequences for those around me. For example, I once got fine dust all over my coat while helping a friend clean their house, and afterward was shopping with them and saw a brush that might serve as a good way to clean it. I wasn’t sure if it would work or not, though, so I decided to just take off my coat and try the brush there first. It worked well, so I bought it.

But I realized it also probably embarrassed the friend I was with, who confirmed after that she wasn’t sure I was tracking whether it would be considered rude to get dust on the floor of the store, or how the other customers would feel about me brushing my coat around them. This hadn’t occurred to me as a thing I should care about enough to have it influence my behavior, so I decided it counted as a blind spot; I agree with the general principle that, if you’re going to break the rules, you should still learn them first, and I think that applies to even informal rules and expectations.

In general having an extra lens on myself and others seemed like a valuable thing, so I practiced more deliberately and explicitly considering my appearance and behavior from the eyes of those around me, then running through different value systems and preferences on how they might feel about the things I do. It’s one thing to consider something’s cost and do it anyway, and another to just take for granted that the cost wasn’t meaningful, and I wanted to make sure I was able to do the former in every case.

Another part of my season included reading Class by Paul Fussell, followed by summing up each chapter in a tweet, along with a quick reaction to them. Fussell breaks up the American social class structure into 9 categories, and I believe many of the insights hold up, despite being from 40 years ago. There are some chapters that are basically just lists of types of clothing or what your house says about you, but also lots of interesting frames on human psychology and culture.

It’s also occasionally quite funny, in a dry acerbic way. There’s a lot of upper brow snobbishness that might make someone feel self-conscious if they care about class, but was just amusing to me (my obscure south Florida university even gets a shout-out/put down!), and there’s a section in one of the later chapters where he boggles at the “inanity” of the unicorn fad that had gripped the middle class in the 80’s that was fun to read, even if I didn’t share his feelings.

In fact, it wasn’t until the final chapter that Fussell described the “tenth class” that made me feel at last like I was being described; in short, people who basically just do what they want, enjoy the good things from each part of society without turning their nose up at any of them, truly don’t care what class they’re perceived as being in, and thus “are the closest thing to free as any American gets.”

¯\_(ツ)_/¯ He said it folks, not me.

Synergy: Aesthetics again for sure, before that season most of the chapters about clothing would have bounced off me, but I could appreciate the points being made better than me-of-a-year-ago.

Outcome: Broadly a success? I guess you’d have to ask others for some of it, but I definitely developed this lens a lot, such that I notice and think of things I didn’t used to, and now feel more like I get why people act and react the way they do to certain things.

If the point was to download that generator such that internalize “class” as an important way to judge others/myself, rather than thinking of it as a game at best or survival strategy or gatekeeping at worst, then no dice. But that was just one potential consideration, and after seeing that, so far as I can tell right now at least, there’s nothing “deeper” there, I’m pretty happy just to have gained some knowledge and perspective. I also have some friends who now seem happier to invite me to fancy dinners and such, which is nice.

Season of Vulnerability

This section threatened to be bigger than the rest of the post put together, so I decided to make a separate post reviewing vulnerability in general, and my relationship to it, which you can read first if you want some extra background.

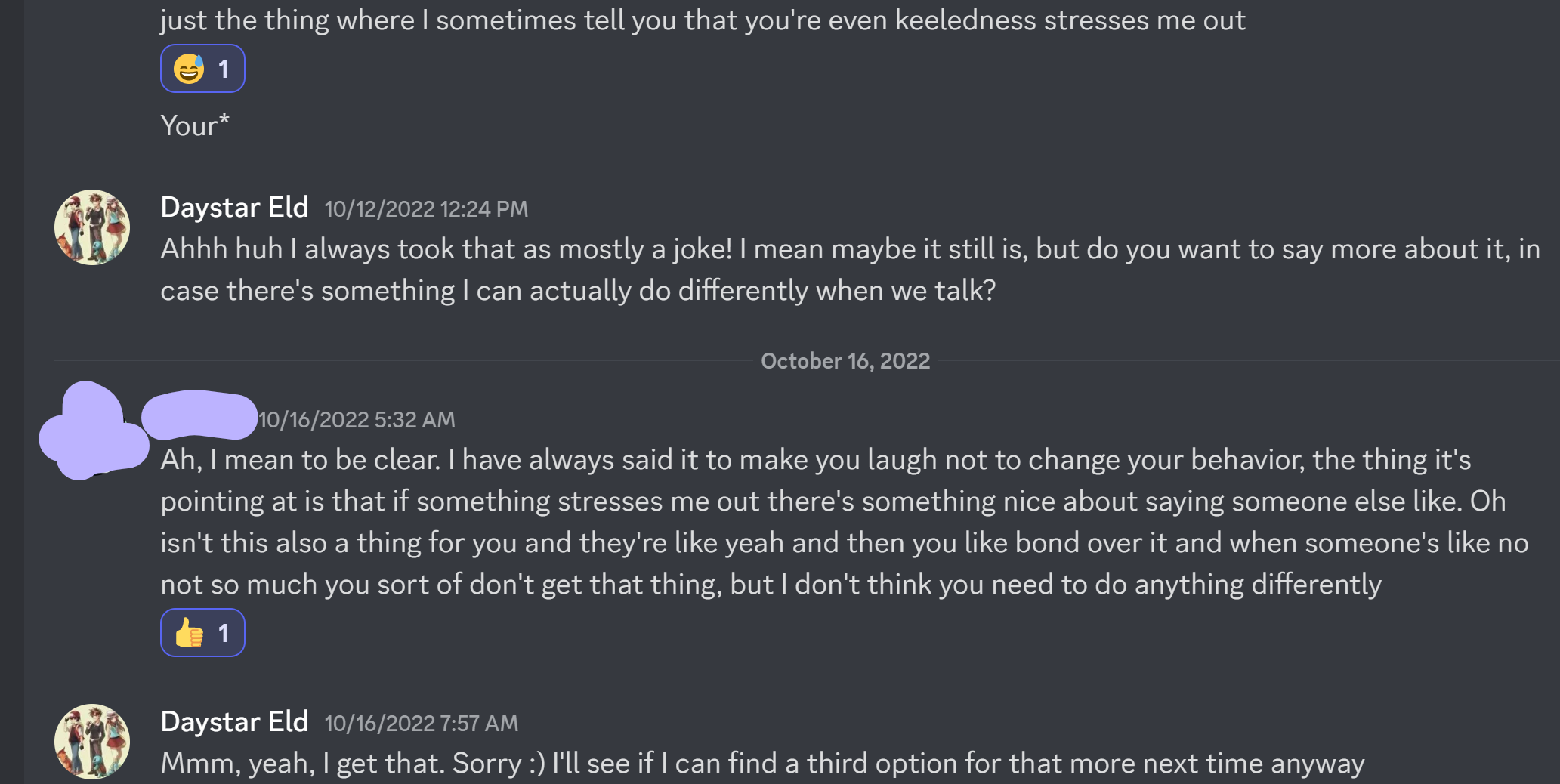

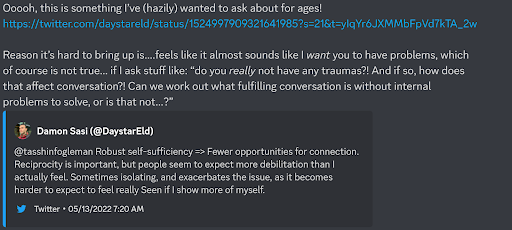

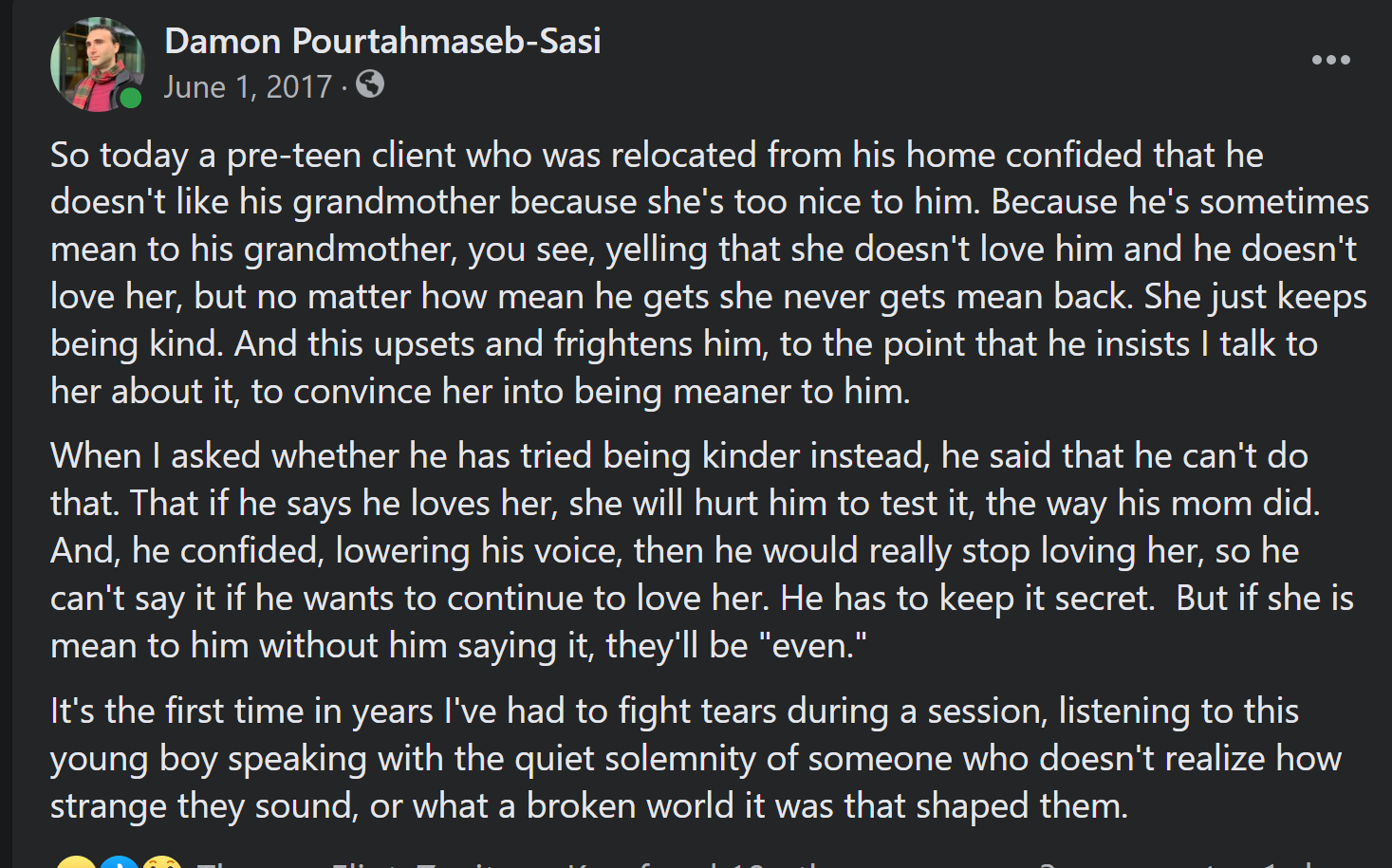

Long story short, I’ve lived my life as being essentially an open book for anyone who wanted to know more about me, and so thought I had sidestepped vulnerability hangups entirely, the same way I have feelings of self-shame or anxiety or major traumas. I started this season because I did some circling with some close friends who confessed to feeling at times like I was too distant and unreachable in some meaningful ways due to me being so self-sufficient. Once I started talking about this explicitly, I got messages like this from a romantic partner:

It reminded me of something one of my exes used to do, which was playfully prod me to “vent” to them more often, even if I had nothing particularly bothering me to share. So I decided that even if I had nothing sad or stressful to vent about or reveal to friends, even if I didn’t feel a “need” to share my feelings, it would be worth trying to share them anyway and see how that felt and was received.

I also started paying more attention to feelings of gratitude and care that I felt for others, and sharing those sentiments when they came up, as well as noticing how I related to others when they were expressing vulnerability. I eventually decided to try alternate ways to develop deeper connections with others.

This led to me trying the VIEW Connection Course on my friend Lulie’s recommendation, which gives people a chance to practice some of the ideas talked about in the Art of Accomplishment podcast. VIEW is a state of mind that invokes higher levels of Vulnerability, Impartiality, Empathy, and Wonder while talking to others. From my experience, I think it’s a great way to improve communication so that more sensitive things can be discussed without defensiveness, and also a great enhancement for things like pair-debugging and self-exploration.

Each virtue mirrors the ones I believe a good therapist should have, but a more personal rather than professional version, better suited for communication with friends. This led to a followup conversation after one of the sessions with Lulie where we talked about how I seem to experience empathy differently than most people: intellectually, but not physically. Lulie noted that this seemed like it would be useful for my therapy work, but left her feeling disconnected at times when she was being vulnerable in some way.

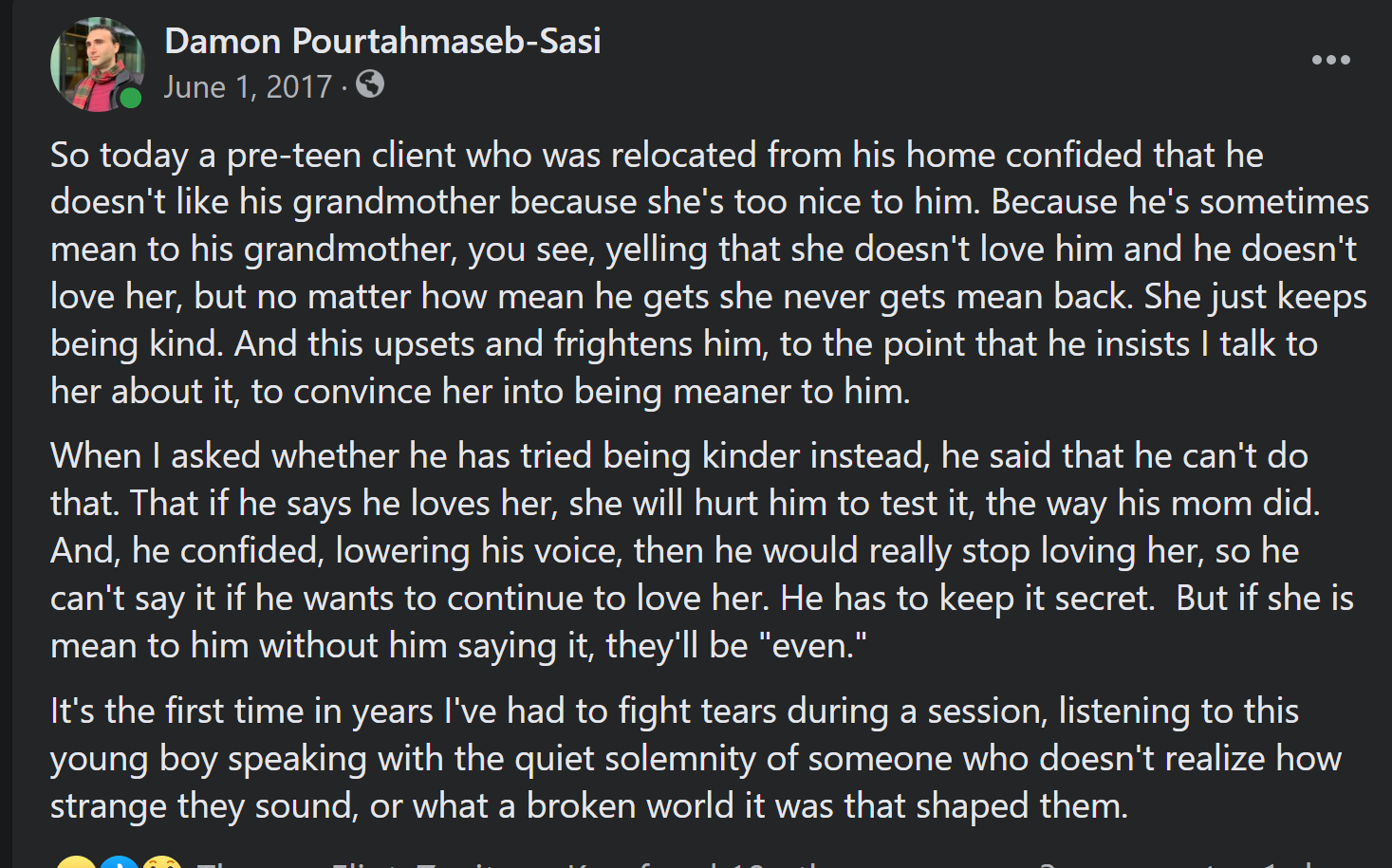

I realized immediately that she was right. When I’m with someone who is sad, I can understand their sadness and want to help them, but I don’t feel it myself. It made me realize that I couldn’t remember the last time I’d cried while someone else was crying. I would tear up sometimes in therapy when my client was relating something traumatic, but only if they seemed to not feel it themselves; in essence it was their disconnection from their emotions that brought me to tears.

But I do cry myself, and fairly often, while reading books or watching shows or films. So the obvious next question was to ask myself why it was so much easier for me to feel bodily empathy for fictional characters.

And the answer, once I thought about it in those terms, seemed absurdly obvious: when I’m with people in real life who are suffering or in need of help, my focus becomes entirely on how to best help them. There’s space for other considerations, but my feelings are set aside for later while I focus on helping the person in need.

But I have no way at all to help fictional characters suffer less. So I’m “free” to feel and share their emotions myself.

This struck me as funny at first, and I began to laugh. It was during lunchtime, and I was in the UC Berkeley cafeteria. After laughing for a bit I began to cry, and couldn’t stop. It felt like machinery in a dark corner of my mind had just had a spotlight aimed at it, and connecting parts began to suddenly make sense.

Growing up, fictional characters felt as real to me as real people. I had a ton of friends at school and in my neighborhood, but when I was at home it was just me and my books. My mom worked constantly, I only saw my dad on weekends (which he spent working constantly), and my older brother and I had let’s-just-say a difficult relationship.

I was in effect raised by fiction, by characters in stories who were both friends and mentors. They showed me what I could be, good and bad, and why I might want or not want to. They showed me mistakes I could learn from without making them, and expressed empathy and understanding for things I hadn’t even felt yet, such that when I felt it I already knew what a good and trusted friend would say, and when others did I was ready to be that person for them.

I didn’t need stories to feel desire to help others, that generator was with me for as far back as I can remember. When I was 8 years old, years before I got into reading fiction myself, I walked into a bathroom and saw a fellow 2nd grader being held against the wall by two older boys. I told them to leave him alone. His name was Matthew, and we became best friends, had plenty of other encounters taking on bullies together, and no amount of hurt made it feel less right.

But physical confrontations were relatively rare compared to all the other hurts in the world. TV showed plenty of heroes that fought with fists, but books gave me glimpses of what else heroes could look like. How they could think, how they would feel, how they would react to those around them when they were in need of help.

I also happened to read a lot of Stephen King when I was young, and King set all his stories in a multiverse that connected all his books into one meta-fictional narrative that included our world as well (not just a version of our world, obviously many of his stories took place in some modern settings, but specifically the world where he, as the author, was writing it).

This multiverse was as real to me as God was back when I was religious, and so the deaths of characters felt real too. There was no one in my life I could talk to about any of it… and nothing I could do to help the characters in it. I was grieving for dozens of people every year, and doing my best to live up to what they taught me. To be there for others in a way they were there for me, and in a way I couldn’t be there for them. Especially for Roland, the protagonist of The Dark Tower, whose ancestral name of Eld I took for my own.

(Daystar is from the book Talking to Dragons, which I read when I was even younger. It’s about a teenager sent into an enchanted forest with a magical sword. He uses the sword to defend himself or others if needed, but always tries to talk first, politely attempting to understand the magical beings around him and find some solution besides violence.)

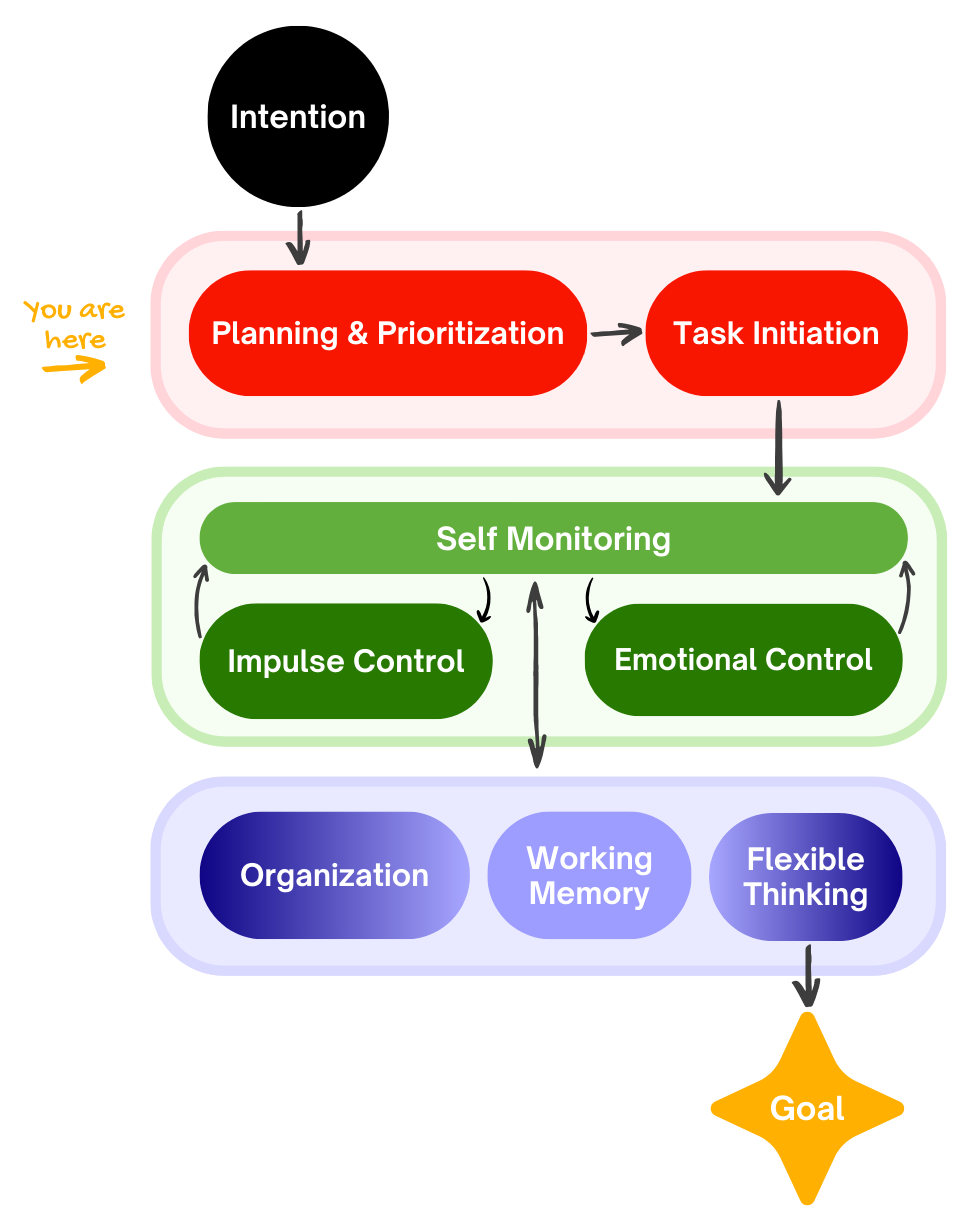

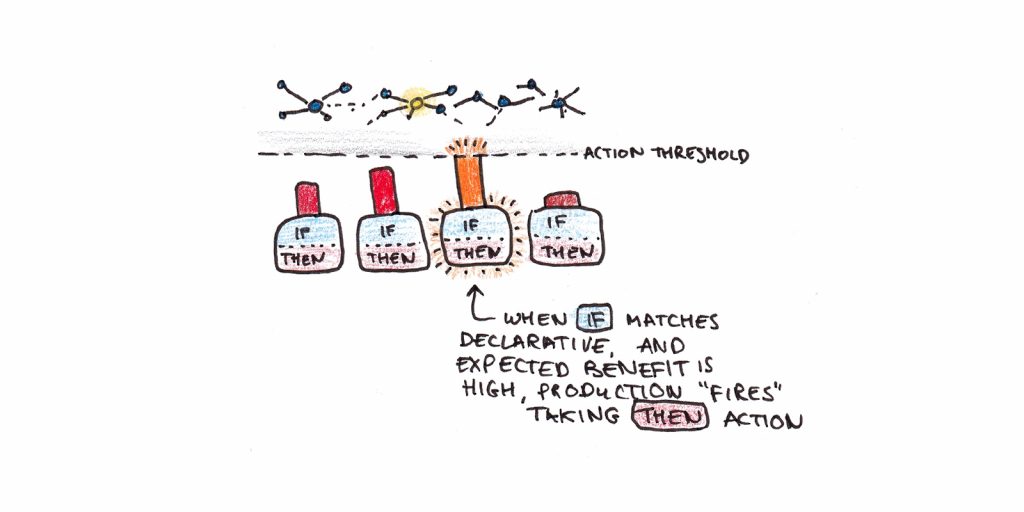

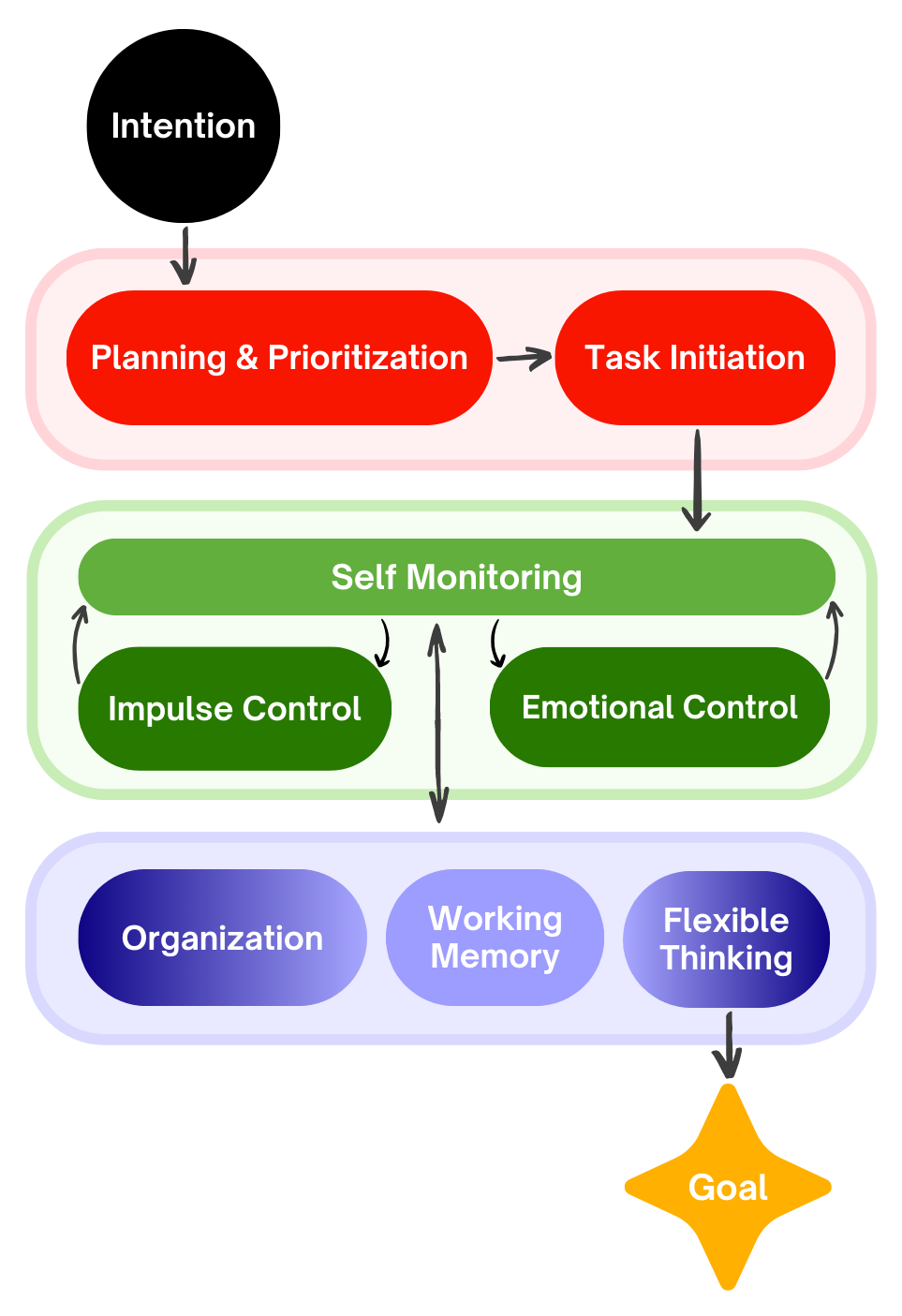

All of these realizations bubbled up and came out over the course of about 30 minutes of crying. Once it had passed, it felt like a new window was opening up in how I related to that fundamental generator in myself. I could better see what fed it, and how the process of [sensed inputs of people hurting] led to [internal alchemy that evoked a state of mind] that resulted in [behavioral outputs in how I responded].

It also gave deeper insight into why I have such strong reactions to particular things in fiction. After watching Spiderman: No Way Home, I tweeted about how much I appreciated it for addressing trauma of characters in previous media… but the underlying emotional effect it had on me was more than that. The best I could describe it at the time was of watching old friends I’d seen go through traumatic experiences, who in essence had their stories irrevocably end in unhappy ways, be given a second chance at a happier one. This season helped me realize how generalized that reaction is, and how deep its roots.

It also gave a plausible story for why I’ve always felt so much older than those around me when I was in school. I used to think it was just living through hundreds of fictional lives + rough home life, either one of which may have been sufficient. But if I take this insight seriously, it could also have been the many, rapid cycles of grief for fictional characters.

So that was all part of the first month of my Vulnerability season.

As a result of it, the next two months involved, in addition to sharing my internal experiences and feelings more often, paying more attention to my inner state when around someone in distress so I could notice when I was entering “guardian mode.” It was surprising how just noticing it made it easy to turn off, and how automatically my body was able to experience things like sadness and grief while the people I spoke to expressed it. This took some getting used to, but has been valuable experientially in its own right.

Synergy: None in particular comes to mind for this one.

Outcome: The first obvious thing is that I have a pair of new internal flags. One of them is noticing when I have a personal thought or feeling that I think the other person would appreciate knowing, and having the decision-possibility to share it. A few people have noticed and expressed appreciation for this, and so I’ve been happy to continue doing it. It’s also nice to share things in more explicit terms when I feel closeness with someone, not just so they know, but also because putting words to feelings can help explore and sharpen them into more powerful experiences.

The second flag is for when someone is sharing vulnerability with me in a way that makes them obviously distressed. At first this happened involuntarily, and it was like I had a new set of mirror neurons that activated automatically whenever someone around me was feeling deeply sad or lost. Now it feels more like something I notice and can choose to have happen. This does mean I sometimes miss the opportunity to do it, but it also means that it has yet to cause any debilitation when someone explicitly comes to me for help.

I also got a nice artifact from my friend Stag to commemorate my growth:

Season of Generativity

This season was inspired by a chat about what the best types of conversations look/feel like, and how things like VIEW aim to give new mental frames and verbal handles that improve conversations along certain dimensions. My partner Eowyn in particular noted that her favorite conversations are those that feel very “generative” in the sense of including each participant’s feelings or experiences of a thing being discussed, rather than just their ideas or knowledge of it. She wondered if there are things that can be deliberately done to make conversations spark curiosity and passion in general, rather than just relying on intrinsic interest.

This caused me to introspect on my own experience of conversations more, both to zero in on what makes the best ones good for me too, and to try and better understand how the things I say might land with others. I began to notice more when someone brings up an idea or asks a question that I answer with just what I know about it, but not how I relate to the topic or how it makes me feel. There’s also a default mode that I tend to slip into, because of the sheer volume of messages I get day to day, of treating each unprompted one as… sort of part of a checklist, like “Okay I answered their question/gave a response to what they said, now it’s off to the next message/thing I have to do until they respond.”

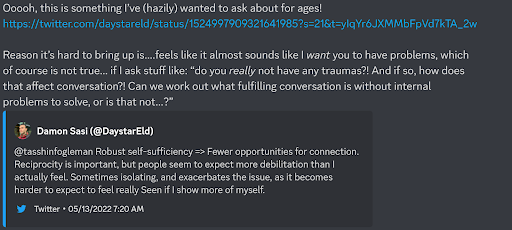

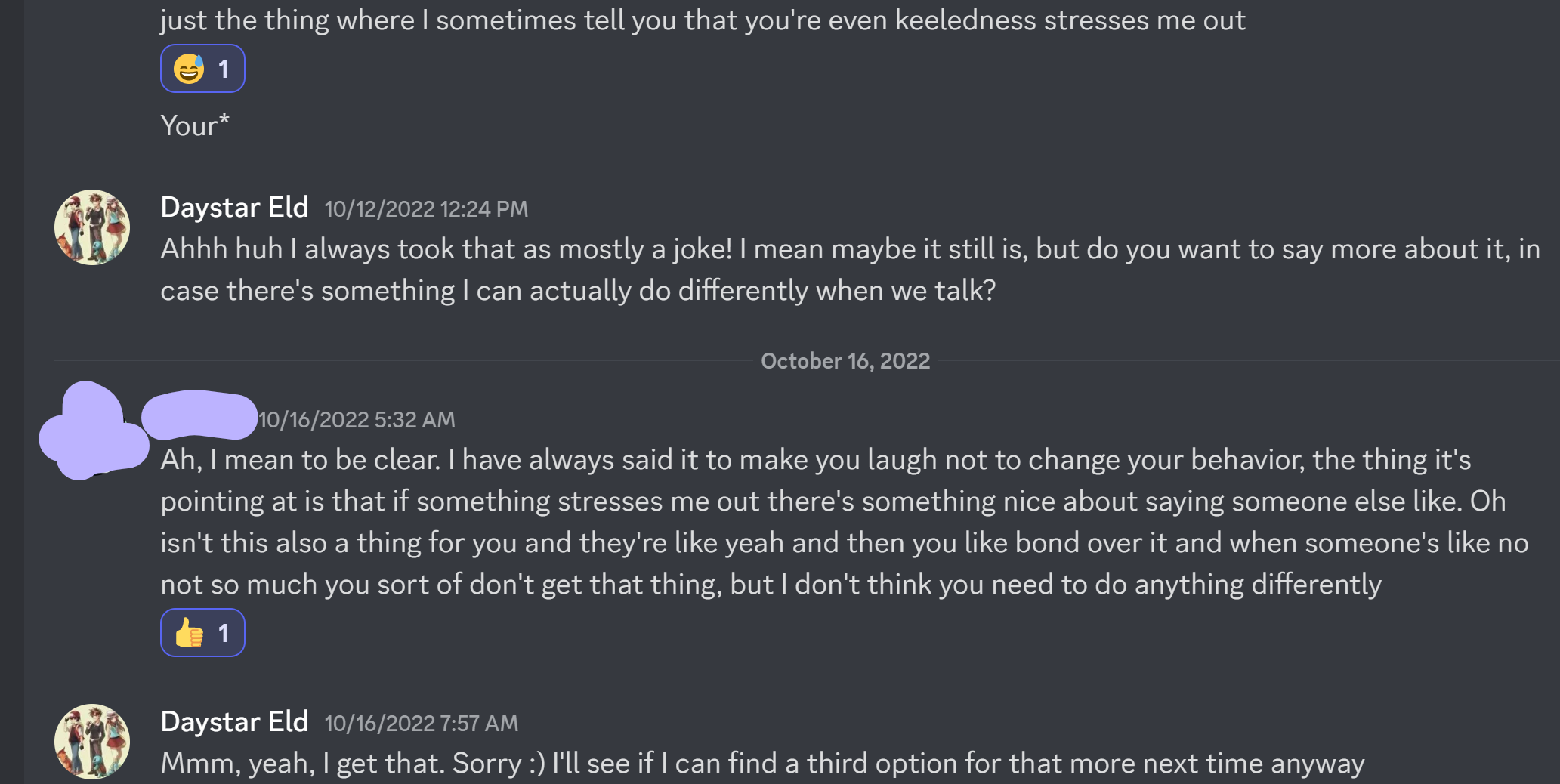

As a side note, one of the reasons I try not to talk about myself too much is because I recognize how much of it can sound like bragging, or can make others feel bad about themselves, or can feel isolating to them:

But part of Season of Vulnerability included not letting that stop me as much, which is why it feels worthwhile, at this point, to mention how my thoughts are never in want of something interesting to occupy them. I am rarely, if ever, “restless.” Outside of very few exceptions, I don’t make bids for others’ attention or feel bad if I don’t get it. Boredom is a foggy memory of being on a long car drive when I was about 8 years old, before I started reading fiction.

As far back as I can clearly remember, certainly within the past decade or so, my life has been one of constant engagement with ideas. Ideas about stories I’m writing or reading, ideas about my work, my plans for the future, some experiences I had, curiosities and mysteries and problems to be solved, imagining other worlds, imagining what it’s like to be others, etc.

And so upon hearing about the way some of my conversations might feel less generative, honest reflection made me realize that for the most part, my responses to people that come off as perfunctory are in fact often (though not always) perfunctory, because my mind is often busy with other things.

My ideal conversations have a back-and-forth flow of expressing ideas. I love arguing over different values, being taught a new perspective, or seeing a new one land for the other person, and having them build on or counter with something else. I love conversations that spark and flow in new, unpredictable directions entirely.

But I haven’t often put effort into making conversations that way if I don’t already feel interested in them, because there are always other things my thoughts will turn to by default that I’m happy to think about instead.

So when I consider the topics that make me “come alive” more than others, what comes to mind are fiction, video games, writing, rationality, romantic norms, psychology, morality, epistemology. For most other things, I might have some intellectual interest that can spark into something more, but I don’t feel like I have the same level of investment/curiosity, and so conversations don’t have that “generative quality” and tend to peter out more often.

A practical benefit of these realizations was that it also helped notice why particular topics fail to spark interesting conversations for/from me, such that this itself can then act as the seed for one. For example, I noticed when the idea of creating new “social currencies” came up in conversation, I felt the urge to not say much in response because 1) I felt skeptical that any less fungible currency aimed specifically to not have market value would ever be widely adopted, while 2) I didn’t know much about the topic, so didn’t want to say anything that might be discouraging without concrete critiques.

The outcome of that, however, would be missed opportunities to learn more about the topic such that 2 wouldn’t be an issue. By trying to manage my conversation partner’s experience I was making them feel bad in a different way.

This is one of the things that gets covered in VIEW, which made it easier to spot, and reinforced the value of avoiding that sort of mistake as a more general category.

Synergy: This season almost felt like an extension of Vulnerability. It built on the first internal flag from there to also notice sometimes when a conversation that didn’t spark “generativity” in me could possibly be more interesting if I lean into my curiosity and try to think about what feels interesting or exciting about the topic to the other person, which is obvious when put that simply but hard in practice when there are a dozen+ other things making bids for attention and are more “obviously interesting.”

Outcome: I’m not sure there’s been enough time since this season ended to really evaluate its lasting impact, but if I’m being honest I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s the least transformative. Maybe because it’s the least impactful day-to-day compared to the others from this year, or maybe it’s just a regression-to-the-mean of how drastic a change I can undergo in a 3-month period. It still feels good to keep it in mind whenever conversations feel stilted, dry, or otherwise less than ideal in some way.

The plan for 2023

Overall, 2022 was an amazing year for me. I spent most of it traveling to teach at and attend various camps and workshops and writing retreats, spent a lot of time with friends I normally only get to see for brief periods, and learned a lot about myself and my interactions with others.

I plan to continue my Seasons of Growth in the new year, though my first Season so far has been one of Rest/Reflection. At first I struggled to think of a new theme to focus on for the start of the year, but realized that after 8 of these in a row, it seemed reasonable to take a break. Further integration and practice continue to yield benefits for all of them anyway, and I’m confident that a new theme will reveal itself as valuable to focus on in time.

I hope others find value in this structure, or variations of it, and would be interested to hear what themes others have found useful for themselves.